Until she married my dad at 18, my mother was Sally Sue Jensen. Afterward, and for the rest of her life, she was Sally Sue Sisson, an alliterative tongue-twister of a name befitting a Dickens street urchin.

“T’was Sally Sue Sisson what picked me pocket!”

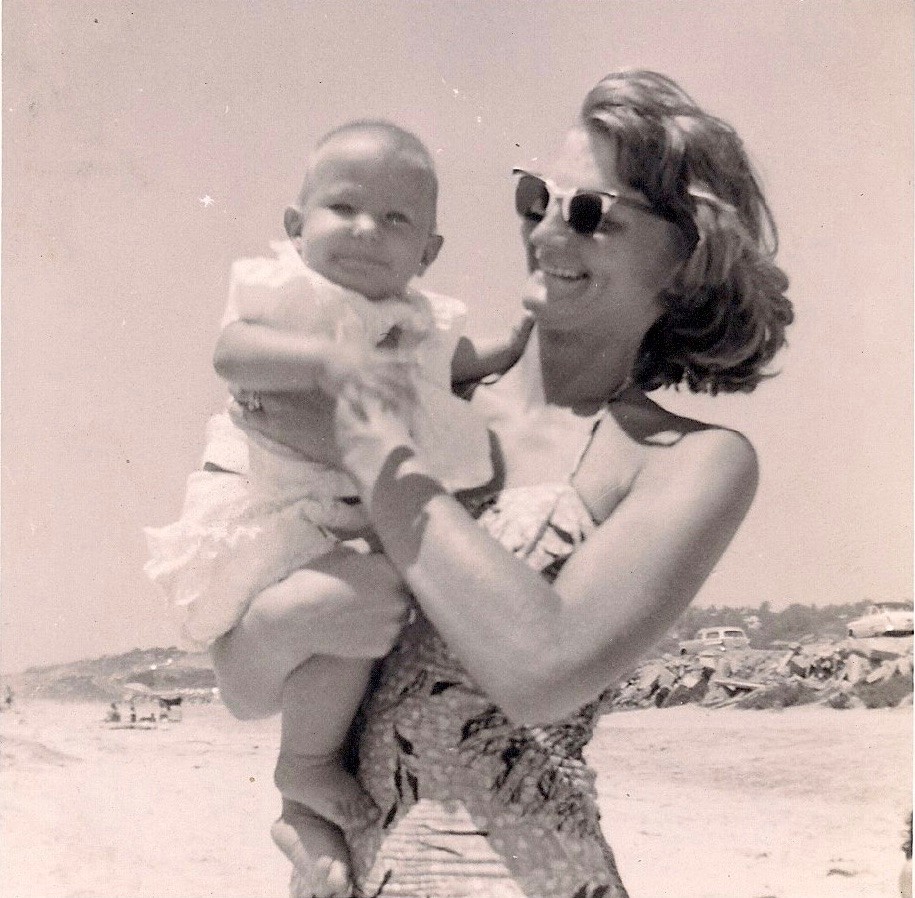

My mother was tall, lovely, and slender with blue eyes and high cheekbones, gifts of her Danish and Norwegian roots. By the time she was 25, she had four children and no time for extras like learning to drive. She was 28 when she finally got her driver’s license.

Our family had one car, a Ford Fairlane, which my dad drove to the Navy base for work. When he was away on sea duty, it sat neglected in the driveway beaten to death by the sun. My mother was in no hurry to get behind the wheel until her best friend pointed out the potential consequences, stressing the urgency with grizzly scenarios involving her children.

“What if you’re home alone with the kids and one of them falls out of a chair or something and cracks their head open. They could bleed to death by the time the ambulance got here.”

My mother dove into her DMV workbooks, marking them up with a pencil. She took her driving lessons filled with a mix of anxiety and determination, instructed by my dad or a helpful neighbor. Pulling away from the curb, she sat straight up in the seat, hands gripped at 10:00 and 2:00, bracing for the slow drive around the neighborhood. After the lesson, she would come home frazzled and cranky. The day she passed her driver’s test she proudly waved her temporary license, and we had a little celebration. But driving would always be a necessary evil for her; she was not one to take a leisurely Sunday drive.

Until my mother had her driver’s license, she would pull us around in a big red Radio Flyer. For the four of us kids to fit in the wagon, we had to wedge in from back to front in birth order. I remember taking my position, the metal bed of the wagon hot on my legs as I settled in. I was at the back of the wagon, my brother, Kelly, in front of me, and so on until all of us were situated. Our legs were splayed and stretched forward; our siblings tucked between them. Connie, the youngest and barely crawling, was at the front of the wagon sandwiched between my sister Tracy and the beach bag full of towels and diapers squashed in at the front.

We would ride this way the two blocks to the beach. I held on to the sides of the wagon and leaned forward slightly to keep my back from banging against the hard frame as it bumped along the sidewalk. The tires squeaked and the axel moaned. Summer aromas of hot pavement, suntan lotion, and a faint whiff of the sea competed with the scent of my brother’s scalp resting under my chin. As the engineer of this little transport, my mother slowly pulled the wagon forward, looking back occasionally to be sure all was well with her passengers. I had a hazy view of her, my eyes squinting in the sun. Her right arm was stretched back, taught with the effort of pulling our weight. She wore shorts and a sleeveless blouse; her arms and legs were slender and suntanned. Her brown hair, hanging free, glowed with hints of gold. Rubber flip flops slapped on her feet, and large black and white sunglasses rested on her nose.

To this day, the smell of metal in the sun will take me back to those sticky rides in the wagon, bouncing along, my mother tireless and most likely humming.

When I was old enough to start school, I walked the half-mile to and from West View Elementary. Back then, it wasn’t unusual to see kids walking to school alone or in groups, carrying colorful lunch pails and maybe a book or two. There was no need for backpacks because everything we required for class was left in the classroom, stuffed inside our small wooden desks.

One afternoon just before school let out, it started pouring rain. As usual in San Diego, it was unexpected and unprepared for. Teachers lined up students under the walkways out of the rain, while parents pulled up, car doors yawning open to allow their wet and squealing kids to scramble in. When no ride was there for me, I reasoned that, with my dad away on Sea Duty and my mother at home with three kids and no driver’s license, I would be walking home.

I bravely faced the torrent and was just beyond the school grounds when a car pulled alongside me, engine running. I was already drenched. My sweater hung limp off my shoulders, my hair was soaked and dripping, my shoes flopped from my feet. I must have looked as pathetic as a 7-year-old can.

The woman in the driver’s seat hand-cranked the window down and shouted into the rain, “Get in! I’ll give you a ride home!” Her hair was up on her head and tied with a scarf. She wore big glasses. She drove slowly along, her arm out the window gesturing for me to get inside. She shouted, “Get in the car or you’ll get pneumonia!”

A girl about my age watched me from the side window in the back seat. I didn’t recognize her through the rain-streaked window. I was frozen with fear. All those warnings my parents drilled into me screamed in my head: never talk to strangers, never be lured by the promise of a puppy, and never, ever get in their car. Was this girl in the backseat kidnapped, and was this stranger looking to grab me, too? I ran full charge into the driving rain, slipping and slopping in the mud, my lunch box pounding on my leg with every stride. The woman took off down the road, probably shrugging her shoulders and mumbling something like, “weird kid.”

My legs were wobbly, and my chest was on fire when I finally burst through my front gate. My mother was standing in the doorway as she probably had been for a while, worriedly peering through the pummeling rain for me to appear. She was holding an open towel, her face a mixed expression of guilt, concern, and relief. I ran into the towel panting and sputtering. She wrapped me up tight and said, “For the love of Pete, you’re soaking wet!” Sensing my anguish, she pulled me forward to look at my face. “What’s wrong? What happened?” She asked.

I spilled my story without taking a breath. I told her that I had almost been snatched by a stranger, a woman with big glasses in a big car, and there was a kid in the back seat, and I just ran and ran and then she drove off, and maybe we should call the police.

My mother looked at me for a long moment. “I think it’ll be okay,” she said, and guided me toward the floor heater. She took off my shoes and socks and pulled my soaking wet dress over my head. She brought me pajamas and told me to put them on before I froze. Pajamas in the daytime? What madness was this? I asked her if I had to go to bed. She told me no, that they were just warm and comfortable, and it was okay to wear them in the daytime. She ushered me to the dining room and dragged a tall gray chair from the corner of the room to the table. It was the kind of chair with the pull-out steps in front. She patted the seat for me to sit. I climbed up and swung my slippered feet from the high chair, watching the rain hit the big windows.

She disappeared for a few minutes, “Stay there, I’ll be right back,” she said. I heard her in the kitchen, emptying a can of Campbell’s tomato soup into a pot. She came back with a comb and a dry towel. “We need to get your hair combed out and dry before you catch pneumonia.” Pneumonia again. She teased out the knots, squeezing each tangle-free section of hair with the towel. She told me how brave I’d been, what a big girl I was, and how badly she felt that I had to walk home in the rain. I nodded pathetically, soaking it all in, basking in her attention. When the soup was ready, she brought it to me in a large mug. No bowl? Very grown up.

I know that my brother and sisters had to be in the house that day, but I have no recollection of them being there. It was blissful and rare to have this much of my mother’s time focused on me alone, so they have been expunged from this memory.

For the most part, my dad was the more openly affectionate parent. You couldn’t walk by him without being pulled into a bear hug or neck noogie, as if he believed we’d evaporate unless he made contact. Maybe it was all the months at sea taking us away from him, or him growing up the only child of older parents. My mother was less likely to hug us for no reason. Her affection was evident when she lovingly applied a Band-Aid to a barely-there wound, stayed up late baking cookies for class, or patiently combed tangles from wet, mangled hair. She balanced the well-being of her family across the board; the kids were like a single entity. Unless it was solicited by one of us, there was not a lot of individual time with her.

When my hair was sufficiently smooth and dry, she put down the comb and hung the towel on the back of a chair. She leaned against the table, arms loosely crossed, facing me. “Tell me about the lady who tried to give you a ride,” she said.

I described the woman in as much detail as I could recall, given that I was drowning at the time. When I told her the car was silver, she said, “Sounds like Karen Freeman’s mother.” I was immediately embarrassed. It hadn’t been a stranger. It had been a mom. And Karen, peering from the backseat window, had seen me run away. I was mortified. I told my mother that I felt really dumb.

“Oh, don’t feel dumb.” She said. “You did the right thing because you thought she was a stranger.” She walked to the phone on the wall and lifted the receiver. She flipped through the phone book with her other hand. “I’ll call Mrs. Freeman and let her know you’re okay and thank her for trying. It was nice of her.” This was the first of many times in my life I would reflect on my behavior and wonder if it had made sense at the time, or if I had been a complete idiot.

Fortunately, that first moment of self-doubt does not overshadow that magical afternoon with my mother. As an adult, I’ve been through harsh times when despair felt like a step up. During those times I turned to my mother above anyone else to help pull me from the pit. Each time I laid myself open to her, sharing the worst of it, she did not offer advice. She would listen while I poured out my pain, and respond with words that soothed and assured me. And each time, I took away a little of the feeling I had the day she wrapped me in a towel, made me hot soup, and teased the tangles from my hair: loved and shielded from the storm outside.

Although my mother might revert to Campbell’s tomato soup in a crisis, she was probably the best cook in the neighborhood. She made simple, flavorful meals she’d learned to cook growing up in the mid-west. The aroma of her pork chops frying in the pan prompted friends to whisper out of ear shot of my parents, “Ask your mom if I can stay for supper.” The answer was usually yes unless there were no extra chops that night. She was a showstopper when she cooked, working in her tiny kitchen with the deft agility of a one-man-band, frying, stirring, boiling, juggling heavy pots and sloshing pans. When my mother was whisking or stirring, she put her whole body into it. Her hips swayed, her shoulders shimmied. My dad got the biggest kick out of it.

After school the four of us kids would take off in different directions across the neighborhood, either to the park or to friends’ houses, until supper time. When it was time for us to come home, my mother opened the back door and whistled a loud trill that carried across the neighborhood. She did not use the typical P-shaped whistle with a bead in it. This whistle sprung solely from her lips and tongue. It had a very specific inflection that could not be confused with a bird or animal. From the time my siblings and I were old enough to leave the house on our own, we were attuned to that sound. My mother’s technique for calling her children home was well known with other kids and parents in the neighborhood. The mother of one of my friends might turn her head toward the sound and say casually, “Terry, that’s your mother whistling. Better go now.” But I would already be gone.

At my mother’s funeral, each of her children spoke. As part of my tribute, I talked about how she would whistle to call us home. From the pulpit, I saw many of our childhood friends in the church nod and smile.

Sally’s whistle. I remember.

My mother developed Parkinson’s disease in her sixties. The four of us rallied around her, making sure she had everything she needed to function the best she could day-to-day. She did not complain. She did not feel sorry for herself. She did not lose her sense of humor even with the worst indignities of the disease. She passed away at 80, twenty years after my father passed. She collapsed while watering her roses. I can’t think of a more merciful and fitting way for my mother to leave this world.

That year, San Diego had one of the hottest summers on record with the humidity level off the charts. We held her memorial service in the church she had attended for years. There was no air conditioning, so it was miserably hot and muggy. Regardless of this, the church was filled with people who’d come to remember my mother. After the service, when everyone had gone home, the four of us, our partners, grown children and grandkids sat in the Parrish Hall and watched the video of still photos we had put together for the service. Photos of my mother in various stages of her life faded in and out over a soundtrack of her favorite music: a black and white photo in her wedding dress standing next to my impossibly skinny dad; posing on the beach surrounded by kids; cooking Thanksgiving dinner and sticking her tongue out at the camera; sitting in the grass with her arms wrapped around her beloved Lab, Abby; and many, many pictures of her holding a grandchild, planting a big kiss on their chubby cheek. As we watched, we discussed the memories the pictures evoked. We took it all in, laughing, dabbing our eyes, making jokes to lighten the heaviness in our hearts, and letting the video run over and over so we wouldn’t have to say goodbye. After a while we grew quiet with our own thoughts, and each of the four of us, now united more than ever as orphans, felt a shift in the universe.

Leave a reply to Cindy Santiago Cancel reply